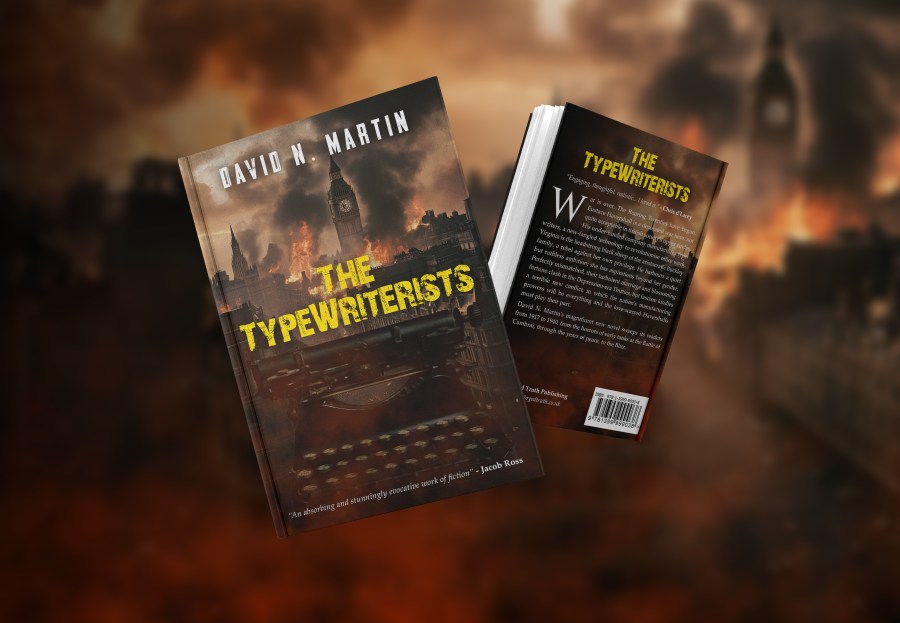

With his new novel ‘The Typewriterists’ now available on Amazon (click here to view), Forged Truth (FTP) took the opportunity to sit down with author David N. Martin (DNM) to discuss the work. Here’s what was said:

FTP: With ‘The Typewriterists’ now published, it has already drawn praise from acclaimed authors such as Jacob Ross and Chris d’Lacey. We know it’s a historical novel, but can you tell us some more about it?

DNM: While I was writing it, friends and colleagues would ask me what I was working on and I would say, ‘Peaky Blinders meets Downton Abbey… with typewriters.’ I’m not sure that’s exactly what I ended up with. It’s a family-based history, and yes, the family business follows the rather grimy typewriter industry in Birmingham from the end of First World War onwards, but I think, at its heart, it’s a love story between Virginia and Eustace Havershall. Not exactly Romeo and Juliet stuff, but definitely a case of opposites attracting and then having to deal with the opposing elements of each other’s character.

FTP: I’d point out that both ‘Peaky Blinders’ and ‘Downton Abbey’ were TV series, not novels.

DNM: Yes, that’s true. I suppose my writing has always been unusually visual and ‘The Typewriterists’ certainly scorches its way through some iconic locations — ranging from World War I tanks, to the grime of Twenties’ Birmingham, to the glamour of Long Island and the Riviera, to the Monaco Grand Prix, and on to the Blitz — that would no doubt make for a great TV or movie adaptation. Here’s hoping, anyway! I have the pictures in my head.

FTP: Can you tell us something about the two main characters?

DNM: Virginia is the American-educated black sheep of the aristocratic Buckley family, seventeen when we first meet her in 1920. She’s very smart, a rebel against her own privilege with ideas deemed ‘unbecoming of a woman’ at that time. As she starts to get what she thinks she wants, she is suddenly faced with the reality that those things come with consequences. For her, I think the book is mainly about discovering that ‘liberation’ ultimately comes with choices and restrictions. She has the courage to face them.

FTP: And Eustace?

DNM: Eustace is a war hero who commanded the early tanks in WWI. He is the unregarded second son of a Nottingham lacemaker, who becomes co-founder of the ‘Havershall & Woodmansey’ typewriter business. He has a quiet but ruthless ambition, born of his war experience which ultimately he can’t shake, even when those ambitions become destructive. He keeps trying to prove himself, over and over again, long after everything he needs to show has been proven. For him, I think the book is largely about how he fights and overcomes the patterns written into his behaviour, when his compulsions start to ruin both him and his marriage.

FTP: Those characters are so richly drawn, but just to return to the setting you’ve put them in. Why choose a typewriter business as the backdrop?

DNM: I originally wanted to write a novel that covered the entire Twentieth Century and it seemed the typewriter was a strong icon for the trends of manufacturing and mechanisation through that period. Not only is it a complex piece of engineering, but its own history starts in earnest around 1900, revolutionises office work after the First World War, peaks in mid-century and is dead by the end of the millennium as computers and keyboards make it obsolete. A lot of the social trends are impacted by or reflected in the history of the typewriter, particularly when you think of the role of women in the work place.

FTP: I know you’ve worked in many industries and even run manufacturing companies in your career. Did that experience influence this book?

DNM: Yes, absolutely. I once ran an engineering company that had started in the Lace Market in Nottingham in the 1920s. Like the company in ‘The Typewriters’, it was founded by two ex-WWI soldiers and descendants of the two families controlled the company until the 1990s. I was involved in moving that company to an old industrial estate on the outskirts of Birmingham which had a history not unlike we see in the setting of Marmaduke Lane in ‘The Typewriterists’.

FTP: Clearly, you could not have written this novel in such sumptuous detail without doing significant historical research. Did that research change your views of the period in any way?

DNM: That’s an interesting question. I think it certainly had a huge impact on the way I dealt with character. WWI was horrific and pointless. Traditional beliefs failed. People had been forced to think collectively, not individually, and long held values of duty to God and country came into question. People came out of that war disoriented. On the one hand, that disorientation created the elitist hedonism that we usually see presented as the Roaring Twenties, but that was mainly the preserve of the upper class minority. Among the general population, it created a renewed sensibility that highlighted ‘family’ and was specifically about repopulating the country. People — men or women — didn’t seem to think so much about their individual ‘rights’ the way we do in the 21st Century; they thought about their place in a world that was rebuilding.

FTP: And you said this shaped the way you thought about characters for your book?

DNM: I think a lot of historical fiction takes 21st Century characters with all our sophisticated beliefs about individual rights and tolerance, and plonks them in a historical setting that doesn’t believe or understand those things. It’s fantasy not history. Not that I’m saying historical fantasy isn’t a valid genre; it is. It just isn’t how I saw ‘The Typewriterists’. I tried to start with raw character types, understand what the influence of their background would be and present them like the flawed human beings I imagined them becoming. In Virginia, I imagined a smart young woman, protected by privilege and — to some extent — trapped in naivety by it, who is desperate for real experience, and is then overcome by reality when she gets it. In Eustace, I found this fundamentally worthy young man who has to carry survivor guilt into his post-war life, and who can’t stop trying to convince himself and others of his worthiness to live and love, even as it destroys him. The reponse to trauma is often a fixed pattern of behaviour, I think, and that’s what we see in Eustace.

FTP: You said earlier that you originally wanted to cover the whole of the Twentieth Century, does that mean there are sequels to come?

DNM: Well, without giving away too many spoilers, I think I ended up with a stand alone novel that comes to a natural conclusion. The main characters find their place in the world early in the Second World War, and that’s where this story ends, but there’s a Havershall family that continues on afterwards and a mystery about what happens in the Woodmansey family, who are the Havershalls’ partners in the typewriter business at the centre of the novel. So… maybe…?

FTP: Thank you. We look forward the the publication of ‘The Typewriterists’. And maybe to that sequel.